Juliana Johnstone - Indian Roots

Juliana Matilda Johnstone was the mother of Annie Janet Birch's (nee Waterlow) mother Jane Maria Waterlow (nee Marshall). Below is a photo that is possibly of Juliana, but we have no way of confirming this.

Juliana was born on Friday 20 Jan 1837 at Mhow in Madhya Pradesh, India "Poona, the lady of Lieut. Johnstone, 10 Regt Native Infantry, of a daughter". Mhow (now Dr. Ambedkar Nagar) had a strong military connection with the Indian Army. Her birth certificate records her parents as "James Johnstone Drummer 4th Company 68th Reg of India and of Isabella his wife. Juliana was baptized 6 Feb 1838 at Chunar Church.

Using the birth and marriage records we can trace where Juliana's family was living in India:

- James Johnstone was born in 1801 at Fort William, Calcutta, Bengal.

- James Johnstone (aged 29) married Isabella Mathew (aged 15) on 5 Oct 1829 in Dinapore, Bengal.

- Juliana was born 20 Jan 1837 in Mhow, Madhya Pradesh.

- Alexander was born 5 Nov 1839 in Allahabad, Bengal.

- Margaret was born 28 Oct 1852 in Augur, Calcutta, Bengal.

- Isabella Johnstone (nee Mathew) died and buried on 25 Sep 1875 in Lucknow, Bengal.

James Johnstone is always list as an infantry drummer in the Indian Army (68th Regiment and later a Drum Major in the 2nd Infantry Regiment) which was a role reserved for Anglo-Indians (i.e. mixed descent). The parents for James Johnstone were "Jacob Johnstone, was married to Lakshmi, a native from Calcutta, and her name was Anglicised to Lucky." Jacob Johnstone was very likely an illegitimate son of one of the Johnstone brothers who had harems in India.

"Unlike other colonies, however, colonial families in British India were often not 'legitimate', in the sense that the parental conjugal unit were frequently unmarried and some men kept several women in a harem-like arrangement." Excerpt from "Sex and the Family in Colonial India: The Making of Empire" by Durba Ghosh.

Charlotte Johnstone (nee Holmes), wife of Alexander Johnstone, at the wedding of Sutcliffe and McCarthy. The woman sitting at the front on the right was Alice Constance Johnstone. Alice was a doctor who didn't marry and travelled to England in 1935 and lived in London, staying at 41 Thistlewaite Road, Hackney (recorded in the 1939 England and Wales Register):

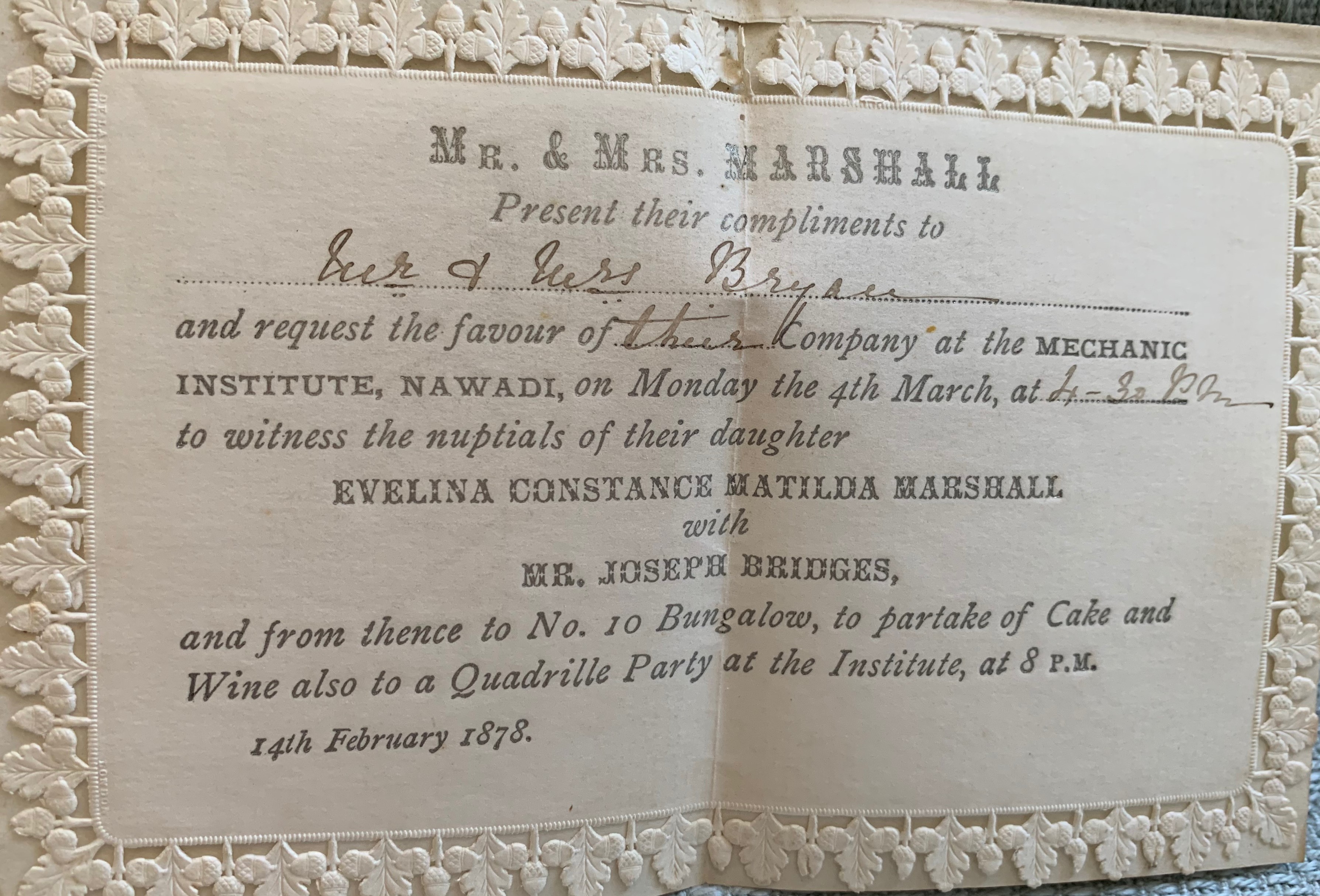

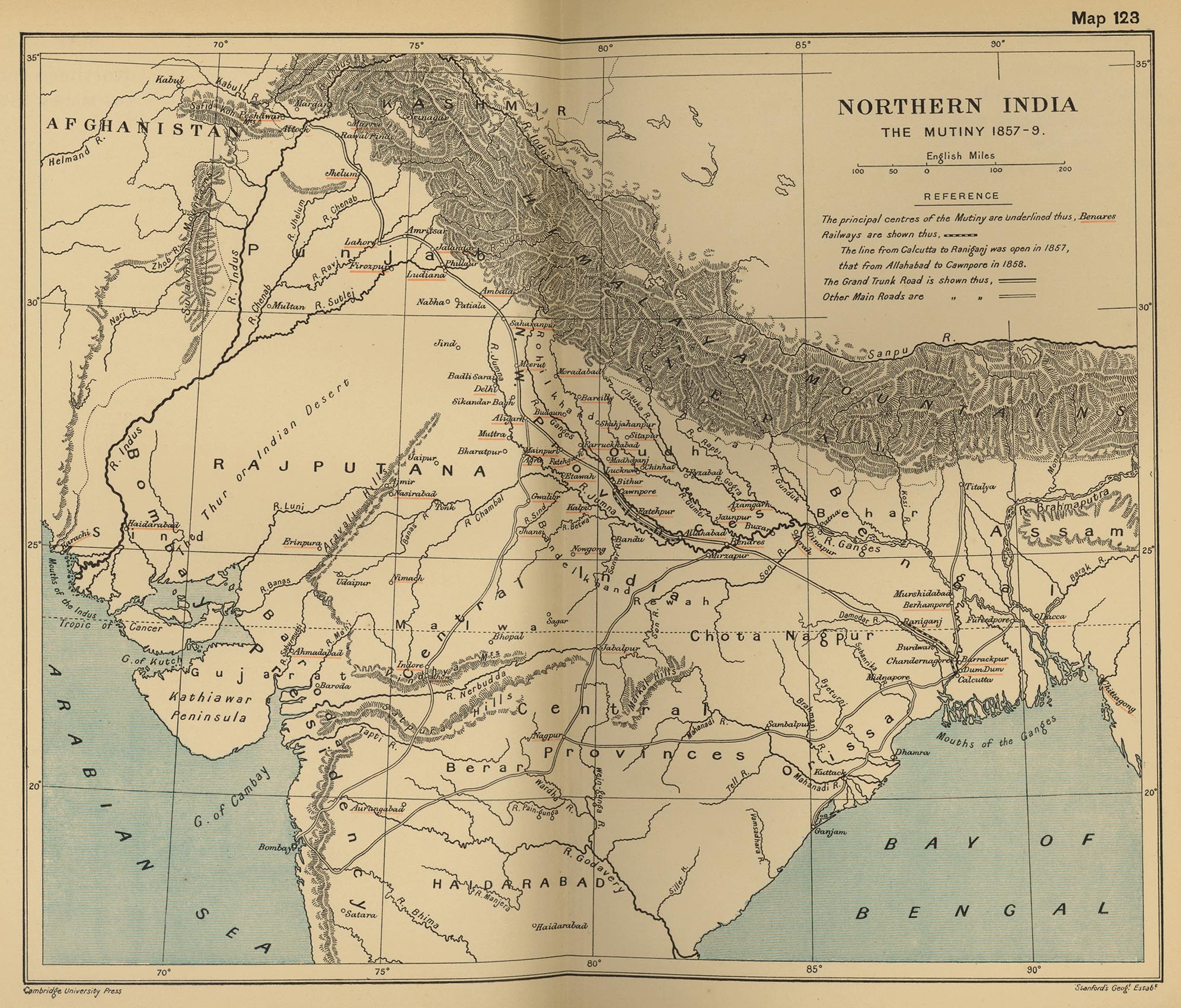

Juliana married John Joshua Marshall on 14 Oct 1852 in Agra, Bengal, India at the age of 15 years old. We don't know much about JJ Marshall. We don't even know if that was his real name as it is suspected that he changed his name. We don't know how he came to be in India. What we do know is that after earlier occupations as a Vet (in Agra) and as a Toll Collector (in Meerut), and before later occupations as a fitter/mechanic for the East India Railway (EIR) (in Allahabad) and mechanic for the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway (in Nawadi, Bengal), at the time of the Indian Mutiny in 1857 JJ Marshall joined up with the Meerut Light Horse. He would certainly have been present at the time of the conflict.

The Indian Mutiny 1857

"A Tug On The Thread: From the British Raj to the British Stage: A Family Memoir" by Diana Quick contains a lot of details including first hand accounts of events in and around Gwalior. Diana Quick is descended from Juliana's sister Margaret.

I don't want to reproduce too much of the book here because it is still in print and well-worth purchasing and reading in full, but here is an excerpt relevant to the Johnstones (specifically Juliana's parents James and Isabella, and sister Margaret) and the Indian Mutiny:

Drum Major Johnstone had been posted to Mhow, a garrison town in the Central Provinces, about eighty miles south of Gwalior in the heart of Maratha India, and it was here that Margaret was born in 1853. When she was four, the family experienced a particularly bloody episode in the Sepoy Rebellion. As the troubles spread from the north and news came in of the mutineers in Meerut and Delhi to the north-west, and Ferozepur to the east, troops started rising in their own part of Central India. It became unsafe for families to remain in the outlying posts, and all who could made their way back to the protection of the Contingent's headquarters in Gwalior.

Isabella and Margaret survived the uprising, but what became of James is not clear. The registers show that by the time Margaret was a fifteen-year-old bride her father was dead but, frustratingly, the relevant file is one of the few that are missing from the India Office, lost no doubt in the aftermath of the troubles. There was every likelihood he had died in the bloodbath; but then, how on earth had Margaret and her mother survived? In order to flesh out the story I had to rely on general reading, and by good fortune came across a first-hand account of what happened to some of the women and children written by Mrs Coopland, the wife of the chaplain. These were the wives of officers and white civilians, and though she does mention that some sergeants' wives and their children attached themselves to the convoy of women who fled Gwalior for Agra, there was no mention of a Margaret or an Isabella Johnstone. I feared that the next part of the story would have to begin with unsatisfactory conjecture, the inevitable outcome of piecing together scraps of information about a family who were, at this stage, pretty well illiterate and thus incapable of leaving any written record of their own. But then a wonderful thing happened: so unexpected, so thrilling, that it sent a shiver down my spine and for days I didn't sleep for the excitement.

The book also provides some excellent background on James Johnstone and his father Jacob:

No one who did not have two parents born in Britain could wield power in the Company any longer. Jacob Johnstone - son of one of the Johnstone brothers - was the grandfather of Margaret, the future wife of Christopher Quick. The only way he and his kind could serve in the military was as fifers, drummers, bandsmen or farriers. Perhaps the thinking behind this was that if you were playing an instrument or looking after the cavalry's horses you could not be wielding a gun or a knife. Jacob became a drummer in the 68th Regiment, Bengal Native Infantry, and in the records of the pension fund his rank is given as a matross - the name, now obsolete, for a soldier of artillery ranked below a gunner. His duty was to assist the gunners in loading and firing the guns, then sponging them down to stop them overheating. They carried flintlocks and marched with the store wagons, acting as guards. Jacob saw active service around northern India and when he died in 1828 his fifteen-year-old son James inherited his post in the 68th. The native infantry liked its drummers to be married, unlike the British army, so James complied by marrying another fifteen-year-old, Isabella; neither of them could sign their name in the marriage register at Myanpoorie.

What was their marriage like? I can never know, but the Calcutta Review of this time suggests that some young wives were scarcely ready for it, like this one, already both a mother and a widow at thirteen: 'You had a good husband, then?' said we, 'Indeed I had, my mother thought he was not kind to me because he used to beat me; but I deserved it well, for I was a great scamp.' 'A great scamp!' we repeated, in some dismay. 'How?' 'I used to be playing marbles with the boys, when he wanted his supper ready.'

I pursued Margaret and her forebears through the registers of baptism, marriage and death in the India Office records at the British Library. On the pages of the marriage registers are only the bare facts - place, date, age at marriage if under twenty-one, husband's occupation, name of the bride's father. Baptisms and deaths are even more meagre, but it is by these skeletons that I have built up my family background. It seems that Jacob Johnstone, Margaret's grandfather, was married to Lakshmi, a native from Calcutta, and her name was Anglicised to Lucky. There is no other information about her, nor anything about her daughter-in-law Isabella. I am convinced that both Lucky and Isabella were not of 'pure English blood', though- their circumstances, married to bandsmen, would mean that they were at most of mixed race, or they could even have been Indian foundlings, Christianised and raised in orphanages in Calcutta, such as Mrs Wilson's Native Orphan School, where the girls were raised as Christians and married off at fifteen to native converts.

I don't know if Margaret's grandmother and mother were, like the child bride described in the Calcutta Review, forced by circumstances to be hardboiled in their attitude to love and marriage, but I do know that by the time Margaret was born in 1853 her parents Isabella and James had lost two children in infancy, but included a fifteen-year-old girl and a thirteen-year-old boy, as well as the newborn Margaret, in their family. They were living during a time of aggressive expansion and consolidation for the Company. There had been the long campaigns early in the century to subdue the Marathas, a warrior people whose territories stretched in a wide band across the whole of India below Bengal, and who were themselves masters of a number of tribes, Bheels and Pindarees as well as Rajputs. The native regiments were also kept busy with a series of military campaigns to acquire native sovereign states.

Map of the Northern India at the time of The Mutiny. Note the locations of Gwalior towards Delhi in the north and Mhow in the Central Provinces near Indore:

The Indiaman - Dreaming of the Past

Mrs Eve Ball (Wragg Cottage, Shrivenham Road, Highworth, Wiltshire, SN7 7QQ) in the Indiaman magazine. Advanced warning: There is a lot of fanciful thinking in this article.

I have an intriguing tale to tell and will try to tell it without making it too dramatic or farfetched.

For three years now I have been trying to discover the true name of my gt. grandfather. I knew from family stories that he was born in the North Yorkshire village of Sledmere in 1820, and worked as a stable lad in the world famous stables of Sir Tatton Sykes of Sledmere House.

My gt. grandfather's entire family worked at this great country house and his father, I presume, was a groom to Sir Tatton and helped his son to train horses.

In 1949 an aunt carried out research on his career in India and found that he married in Agra in 1852, and his profession was given as a civilian Veterinary Surgeon. His daughter, my grandmother, was baptized in Meerut in 1957, his profession being given as 'Late Toll-keeper, Boolundshuhur and now of the Meerut Light Horse.' Furhter research on my part revealed that he was mentioned in despatches during the Mutiny and was awared the Mutiny Medal.

He apparently ran away from home, at what age I don't know, and was recruited into the army. It is at this point in his life where his true identity becomes an enigma, as he changed his name to John Joshua Marshall on joining the army which made it impossible for his parents to trace him and buy him out, as they evidently tried to do.

For the past three years I have researched life in india, but have not succeeded in discovering which regiment he joined or even where in Yorkshire he was recruited. However, I've now accepted the closed door on his 'India life' and have concentrated on researching his birth and life in Sledmere.

I've looked at 1820 births in Sledmere; I've visited Sledmere House where I saw a potrait of Sir Tatton with one of his racehorses and groom, John Snarry, standing beside him, so off I went and researched the entire Snarry family of four sons all of whom worked and were connected with the stables.

At last I was convinced that I had found my man but my hopes were dashed when I visited a churchyard in Malton, Yorkshire, and found John Snarry junior's gravestone! By this time I had become pretty obsessed about this man's identity and found myself thinking about him even before falling asleep.

This brings me to the intriguing bit .... I had a most vivid dream, in colour, of a stone wall covered in dark red ivy and everywhere I saw leaves in varying shaeds of red. I don't ever remember dreaming in such vivid colour so began to think J.J.M's name might be associated with the colour red! I researched names like Redhead, Redwood, Hughes (hues) and even Herring (as in red herring). Needless to say, I found nothing. A few months later I had another dream - this time a yound man in a white shirt and brown breeches was seated at a table covered with a red cloth on which was a piece of notepaper. He brought his fist down hard on the table and said: "You will never know my name!"

On reflection I reckon I completely misinterpreted the meaning of the red leaves. I read Andrew Ward's book 'Our Bones are Scattered' shortly after and was shocked at this horrific tale of torture and killing during the 1857 mutiny and immediately felt the vivid red in my dream was J.J.M's message to me of teh violence and bloodshed of that fearful time.

I shall always wonder if my dreams were brought on by my own obsession or could there be a touch of the paranormal in them? I've several more 'Indian' ancestors to investigate so will continue on my seemingly endless research.

I wonder if any other readers have had similar puzzling experiences?

Blue-Eyed and Brown-Skinned: Uncovering a Hidden Past

Extracted from "Kunapipi Vol. 25 2003".

My name is R— . I was born in England in 1964. and this is my story. As part of my immediate family would be most unhappy if they knew I'd written it, I will withhold names to respect their privacy.

On the 1st of January 2000. I made several New Year's Resolutions; among them was a pledge to solve the mystery of why half my family is 'coloured', that is, has dark skin. All I knew about my family was that my father's family was English-born and bred, and that my mother was born in India and emigrated to England in 1948. She met my father there in the late 1950s, and the rest is history. My mother's maiden name was Dobson and I knew she must have been born in the last years of the great British Empire, when the sun was rapidly setting on it, even though, just a little while before, it had been guaranteed never to do such an awful thing.

Upon Indian Independence in 1947. my family from India was broken up. My maternal grandfather's brother 'stayed on' in Calcutta, while my Nan's sister and her mother went to New Zealand. My own maternal grandfather and my Nan, my maternal grandmother (whose maiden name was Waterlow) and several cousins emigrated to England. In total, six adults and two children stayed in England, while the others later decided to join the rest of their family in Australia and New Zealand. The colour of my mother's side of the family ranges from white to dark brown, with several shades in between. They never concealed the fact that they came from India, and they kept in regular contact with the branch of the family still in Calcutta.

I always had a fascination with India because as a child I would spend many weekends visiting or staying with my Nan who would tell me wonderful stories of how different life used to be in her childhood, of how she was free to roam anywhere without fear of attack or abuse and of how she met my grandfather, who was a friend of her cousin's, at an apprentice's ball in Jamalpore. My grandfather had wanted to be an engineering apprentice for the railways but had to settle for a printing apprenticeship.

As a child I grew up with my mother, father and sister in East Anglia, a very rural part of England, and never thought too much about who or what I was. It wasn't until I went to the village school in Parson Drove that I realised I was slightly different from my classmates. They gave me two nicknames which stuck. It was 1972, when I was eight years old, that I was first called 'Curry Powder'. I thought that I was being called this name because curry was indeed a part of my staple diet — we would have it two or three times a week at home. My immediate reaction was to stop eating curries as I thought this would stop the name-calling and allow me to fit in with the rest of my classmates. It didn't. Then, in 1976 I went to the Queen's Boys' secondary school, and immediately received the nickname 'Black Man'. I was twelve years old and I understood that my skin was darker than the rest of my school friends and was not bothered at all by the name, just accepted it.

The first time I asked my family the reason why we are coloured was about this time. My Nan's brother, Uncle Sid, had just been to visit and I remember asking why Uncle Sid was so dark compared to the rest of us. And I was told that the family was cursed by some magic man in the nineteenth century while they lived in India and that the curse should have stopped with my grandmother's generation. As a young twelve-year-old boy I believed every word of this explanation and did not question it until I was about fifteen and no longer believed in curses or magic. Then, I decided to ask my mother's brother Thomas if he could tell me where the colour in our family came from, and he told me we were of Maltese descent. I then went round to my Nan and asked if what my uncle had just told me was true. She sat me down and explained that my fourth great-grandmother was Maltese. And this story too, I believed — at least for the next five years. In 1981, the first time my English-born, English-bred, English rose wife-to-be met my family, she asked if we were Indian. I explained that part of my family came from India, were 'born there', but that we were of Maltese descent and that was where the colour came from. As for the accent, Mum came from India so we were bound to sound like Indians. After a long discussion she believed what I had told her.

In 1989 I was newly married, 24 and desperate to go to the amazing country where my mother's people had lived, to see it for myself. In April I set off with my new wife to explore India. When I told my family that I was going to India they seemed very happy and excited that I was going to visit the family in the country they called 'home'. My Nan also decided that I needed to know some basic Urdu and set about teaching it to me. I must confess I was totally useless at trying to speak the language, and I suppose she must have realised this too, as after several attempts she gave up.

On our arrival in India my wife again raised the question of my origins; she told me that I had 'Indian hands'; she asked me to compare my hands with hers and those of the locals in Claridge's Hotel where we were staying in Delhi. I knew that my grandmother had been born in Delhi, so that was where we started our trip. After several comparisons with the people around we decided that not only did I have 'Indian hands', I had Indian legs and feet as well. This discovery was starting to throw the story about the Maltese ancestry out of the window. Quite separately from discovering that I have a lot of Indian features, I found India difficult to come to terms with. The country is rich with natural beauty, but I was exposed to a degree of poverty that I had never known could exist. It really was a culture shock, and I must say, my trip to this foreign land completely changed my way of thinking about the world. We found Delhi to be very beautiful, and you could still feel the British influence on the city and could imagine how life would have been during the British Raj. We spent three weeks exploring Uttar Pradesh and then decided to visit the family in Calcutta. Compared to Delhi. Calcutta was a different world, one that my wife found very difficult to adjust to, for the pollution and the sheer volume of people sleeping out on the streets were shocking.

My maternal grandfather's brother was retired and in poor health due to tuberculosis. He was living in Circus Avenue, Calcutta - with his son who is a manager in an electrical repair store. The rest of the family were in good health. The thing my wife and I found most strange about our relatives in India was that they would emphasise being British at every opportunity that they could get, though they never said that they wished they had gone to England. I remember finding it most strange when they told me. 'You just can't get decent servants these days!'. My wife and I found this comment quite amazing as we had never experienced the services of any sort of servants, and we could not believe that decent or indecent, they still existed in India. We stayed with my family for five days only. We were supposed to stay longer, but Calcutta was starting to get to my wife and she was desperate to leave it. We told the family that we wanted to visit Darjeeling to see the Mount Hermon School that my mother had attended, but the family persuaded us not to go as they considered it too dangerous. They told us that several people had been murdered en route to Darjeeling and that they thought that it was too risky for us to go there.

During our stay, the subject of each other's colour and accent was never mentioned. The accent of these relatives was the same as the rest of my mother's family, and I felt that they were my family and no different from the rest of us back in England. On my return to England, I asked my family if we were part Indian in any way. To me this was quite a logical question, as we certainly seemed to have Indian features and my mother's side of the family came from India. My mother denied this and told me to speak to my Nan. Nan refused to listen to my questions and again told me we were Maltese. My family's response to my question was in fact quite amazing. They became very defensive. To be honest, I didn't buy the putative Malteseness for one moment any longer, but I decided to let it drop rather than cause an argument, and I was more interested in raising a family than tracing my roots.

It wasn't until some eleven years later that I returned to the question of origins and made a pledge to solve the family mystery. I started by asking my Nan if she had any family records that I could use as I wanted to trace the family. With some reluctance she produced six pages of handwritten information on the family, going back to 1830. The pages said that William Johnstone, an Englishman, worked for John Company and had a Maltese wife. Nan told me that her mother had written these records to help my Nan's brother get in to the British army. Apparently, they would not accept him to start with, as they thought he was a native Indian. The record was a list of paternal and maternal ancestors going back to 1830, listing their names, occupations and other details. After studying it I decided to ask Nan some questions about William Johnstone's descendants. She told me that she knew nothing more about the family and gave me the phone number of my Uncle Bob, telling me to phone him as he knew a lot more. Uncle Bob is my Nan's first cousin who came from India to England at the same time and lives in Leicester.

After a brief conversation with Uncle Bob, he sent me a copy of all his records, going back to my fourth great-grandfather, James Johnstone, who was married in 1830 to a 'wife unknown'. Uncle Bob had also written a document entitled 'Introduction to the Family in India' to explain how the family came to be in India. There were two things that I noticed about Uncle Bob's records — one was that he had a different name from my fourth great-grandfather — Bob had a 'James', while my Nan had a 'William' — and the other was that he had included several paragraphs about Anglo-Indians (that two seats had been reserved in the Indian parliament for the Anglo-Indian community when India gained independence), though he did not state directly that the family was Anglo-Indian or connected to Anglo-Indians.

Armed with both sets of records I went to the Reading Rooms in the British Library in London to go through all the records there on the British in India. I was trying to find an Indian or Anglo-Indian ancestor, but failed, so I thought, to find either. But I did manage to find a James Johnstone, a Drum Major in the 2nd Native Infantry and his two daughters, Matilda and Margaret, who both ended up being my third great-grandmothers, as my grandmother's parents were second cousins. The Reading Rooms had the complete set of microfilms on births, deaths and marriages in India, and because I knew the name and birth date of my third great-grandmother, Margaret, from my Nan's records, I was able to find Margaret's birth certificate. From this certificate I found the correct name of my fourth great-grandfather and grandmother too. These names turned out to be James — not William — and Isabella Johnstone. From this finding I knew that my Uncle Bob's records were correct and that my Nan's mother's information had major flaws in it.

On my return from London I was a little disappointed as I had not found any Indian or unmistakably Anglo-Indian ancestors, and when telling my story to a friend he suggested that I entered the word 'Anglo-Indian' on the internet to see if we could find anything. I was absolutely amazed to find around forty sites on Yahoo about Anglo-Indians and one entry on the Rootsweb listserv archives. I decided to log on to the Rootsweb and track it to see what it was about. The Rootsweb is a site on the internet where, on its India-list, people researching the British in India can talk to each other. After I had been on the internet, I realised not just what an Anglo-Indian was but what Anglo-Indian attitudes often were about their mixed-race heritage, and I thought it more than likely that my family were indeed Anglo-Indians, and that Anglo-Indianness would answer all the questions that I had been asking the family, including the one about why I had failed to get a reasonable answer for all these years. I remember thinking, 'So that's why we have English surnames, but are brown in skin colour, and that's why my family insisted so strongly that they were British' — Anglo-Indians are, traditionally, more often than not ashamed of their "touch of the tarbrush' and have, till very recently, done their best to conceal it rather than talk about it, much less go searching it out.

Another web site listed about six contacts for Anglo-Indians in England, so I decided to contact each in turn. As I worked through the list I became more and more despondent, as each person in turn told me that their organisation no longer existed. Last on my list was the 'British Ancestors in India' contact name, Paul Rowland. Paul explained to me that the British Ancestors in India organisation, too, no longer existed, but that he was still publishing a magazine called The Indiaman Magazine. I told Paul that as James Johnstone was my fourth greatgrandfather on both sides of my family, meaning that two of his daughters ended up as both being my great-great-great-grandmothers (what a co-incidence!) I had decided that I wanted to research him. Paul asked if I had another name for him to look up. John Joshua Marshall, one of my third great-grandfathers, married James' daughter, Matilda, and I so I said, 'JJM.' I had found some fascinating information about him already. He started his life in India as a farrier before becoming a veterinary surgeon. He then served in the Meerut Light Horse during the Great Mutiny. After the Mutiny he went into horse breaking, and then spent his final years as an engine driver for the East Indian Railways. Nan's family records stated that JJM served in the Meerut Light Horse, and she had also provided me with a copy of a letter from the British Government thanking him for his service during the Mutiny.

Five minutes after my conversation with Paul the phone rang, and it was Paul again. He told me that a lady called Eve had written an article for his magazine about the Khaki Ressalah, also known as the Meerut Light Horse, and that her ancestor was one John Joshua Marshall. I couldn't believe what I was hearing, for as far as my family knew we were the only descendants of the offspring of John Joshua Marshall. Paul gave me this lady's phone number and I phoned her straight away. It was truly fantastic as this lady turned out to be my Nan's second cousin and was living in England in Yorkshire about 250 miles away. We decided to exchange family records. I also asked her if she knew where the family colouring came from, but she just laughed and said she did not know. The good news was that in her records was a letter to her from Donald Jacques, a well-known genealogical researcher. He had found James Johnstone's marriage certificate to Isabella Matthew in Dinapore on the 5th of October 1829, so I now had a maiden surname for my fourth great-grandmother. He also said in his letter that he thought James was an Anglo-Indian as he was a drummer, and Anglo-Indians were often drummers in the army. I was now totally convinced that my family was Anglo-Indian and decided to tell them what I had found. My first approach was to tell my mother that I thought we were definitely Anglo-Indians, and I had a long conversation with her in which I gave her all the reasons for my conclusions. My mother's reaction was to reject totally what I was telling her. I realised that I had hit a raw nerve and decided not to push the subject any further. As my mother was not interested in what I had to say about my findings about the family history, I decided to go and see my Nan and my mother's brother Uncle Thomas again and try to tell them what I had discovered. I had just started to explain my findings when my Nan interrupted me, and said in a very loud, firm voice, 'We are Domiciled Europeans, not Anglo-Indians. We are not Anglo-Indians'. I decided to drop the conversation as I knew it would get me nowhere, but at least my family had given me a term other than 'British' to explain what we are.

So I decided to look into what a 'Domiciled European' was, and I found an organisation on the Internet called the 'Anglo-Indian and Domiciled European Family History Group', which is run by Geraldine Charles. When I phoned Geraldine, I told her that I thought my family was Anglo-Indian and that they claimed that they are Domiciled Europeans. Geraldine explained to me that Domiciled Europeans originally started off as being white Europeans that had settled in India, but as time passed Domiciled Europeans intermarried with Anglo-Indians, that it always was difficult to distinguish between them, and is today even more so — and that though Domiciled Europeans insisted on distinguishing themselves from Anglo-Indians, they always had the same legal status. In other words, today most Domiciled Europeans are indeed, Anglo-Indians who reject the term.

After surfing the web a little more I mustered up enough courage to phone Uncle Bob to ask his opinion about the Maltese descent mentioned in my Nan's papers. Uncle Bob told me that he had never heard of the Maltese story and as far as he was concerned too, we were of Anglo-Indian descent and that was why he had written about the race in his introduction to the family in India. I tracked the India-list on Rootsweb for about three months and then decided to put out a message on it. I received three replies, and one turned out to be from my Nan's first cousin Basil, in New Zealand. At this point I was really in luck, as he had been researching my family for over ten years and had a much better understanding of it than I. He was quite open about the family and confirmed that James Johnstone was indeed an Anglo-Indian and that was indeed why he was a drummer in the army as Anglo-Indians were only allowed to be drummers and fifers. I had definitively solved the mystery and my quest for an Anglo-Indian ancestor was complete. I had now found a knowledgeable member of our family who was willing to be completely honest, open and proud of the family history.

Bas told me that for some reason all the female members of our family have difficulties in coming to terms with what they are and have chosen several different ways to hide their roots. My mother would tell me of how the family had lived in India with servants and that she had attended boarding school there, but that when they arrived in Felixstowe, they spent their first months living in nothing more than a garden shed, and were subjected daily to racial abuse. Could this be partly the reason why my family decided to try to conceal their identity? In early 2001, I sent a post to the India-list explaining my circumstances and asking for Anglo-Indian recipes, because I am interested in expanding my knowledge of both Anglo-Indian history and culture. Family from New Zealand have helped, and friends from the India-list too. I received several replies to my post. One was from Sanjay Sircar in Australia. Sanjay was interested in my request and helped me by email — it is he who is responsible for encouraging me to write this story, and without him, it would never have been written down. Sanjay explained that he is an English-speaking Indian Christian, something completely different from an Anglo-Indian — 'adjacent minority communities', he called them. He believes in trying to understand why people conceal their identities rather than jumping to judge them adversely, and that he also believes that whatever their reasons, the choice is their own to make, and must be respected, whether we approve or not. He also taught me that the Mutiny is now called the 'First War of Indian Independence' by historians, and that many feel continuing to say 'Mutiny' is a retrograde thing to do.

On a lighter note, Sanjay taught me how to make an authentic vindaloo, spicy sweet-and-sour, and when another member of the India-list asked for a recipe for 'tepari jam ', the gooseberry jam that they made in India, Sanjay sent one that he said was Anglo-Indian to the core — with cinnamon-cardamomcloves and whisky or rum in it as well, and told me how Anglo-Indians pronounced the word 'tip-pari', with the accent on the second syllable rather than the first. I had no idea that the gooseberries had anything to do with India until I took some in for Nan to try just the year before (2000). She was over the moon about them, and told me how she used to eat them in India. It's funny, sometimes, how life works out, and I surprised her with some jam when the next lot of gooseberries had ripened well. One crop was very poor, but I was ultimately successful in making the jam as per the recipe — I guessed at the amounts to put in but it all seemed to work, so we had gooseberry jam on toast for breakfast and it was pretty damn' good. Nan also mentioned that they ate Hunters Beef for Christmas, a dish I've never heard of, and we've tracked down a recipe, involving a deboned round of beef hung for a day or so, powdered saltpetre, coarse sugar, cloves, nutmeg, allspice and salt rubbed into it and turned and rubbed for a few weeks, dipped it into cold water, bound with tape, put into a pan with a little water, covered with a brown crust and paper, and baked for five hours. Saltpetre is not exactly common here, but my mother has said that if I get her the ingredients she will make it for Nan.

So one Indian Christian had entered my life, and strangely enough, two weeks later, I received an email from my Nan's cousin Bas explaining to me that my fourth great-grandmother Isabella - the wife of the James (not William) Johnstone - was an Indian Christian from Lucknow. Bas told me that his grandmother said she could not find a maiden name for Isabella when he tried to do a family tree in 1945, and that Isabella may have been one of the female foundlings in religious institutions. Presumably it is Isabella who is responsible for the family's second language being Urdu, as Nan always said.

I tried to get my Nan to tape her stories about life in India, but she refused to do this because she claims that she has a chi-chi accent (but hey she is not an Anglo Indian, which I find so funny!). She does have a strong chi-chi accent — or at least a non-British one — but what does that matter? Personally I love to hear the singsong 'chi-chi' accent as I associate it with the love and warmth that my grandparents have always given me. My Nan's English has changed since I was a child, but I can always remember how I used to find it quite funny that my grandparents would put sentences together using a different syntax from the one we heard around us, speaking arse-about-face so to speak (and I mean no disrespect by using this colloquial phrase). So, when I tried to get Nan to write about her life in India, she first refused to put pen to paper, on the grounds of accent, but after a little persuasion, I saw her one night and made my first recording of her direct. Then, at the end of my visit, she said, 'You will not be needing my book then,' and produced a book with about twenty pages of writing. She is writing her life story for the family, and I am so happy. One other thing Nan says is that her half-sister's grandmother was an 'Indian Princess'. I will try to prove her right. We shall see.

There was a programme on TV as I was writing my story called 'Trading Races', about two white English people swapping colour with a black African and an Asian. The programme was trying to get both parties to feel what it is like to be the other person and to live in their communities. It was very well put together and tried to tackle a lot of the racial problems that exist here today in England. And it got me kind of wondering as to where I actually sit, as I am not a white Englishman nor a full blooded Asian but kind of somewhere in the middle, not belonging to any stable grouping. I am Brown British, and look upon Asians as cousins. When I saw this programme, my question was, was it the same for the Anglo Indians living in India under the British rule, being neither one or the other? Sanjay said, 'As long as you are happy, what does it matter where you sit? We are all situated between something and something else, if not racially (which is really only a matter of appearance), then culturally or in some other way', and it is something I must think about. I also wonder whether Anglo-Indians living in India under British rule, who formed an inbetween community, the ones who were happy and well off serving the British, with job reservations and so on, identifying with the white rulers and sometimes looking down on and bullying the 'natives', sometimes completely denying any and all Indianness, ever envisaged an independent India and their place in — or out — of it.

As for myself, I'm glad I asked my questions as a child, glad my wife remarked on my 'Indian colouring' and 'Indian hands', and I'm proud of being Anglo-Indian, brown-skinned and blue-eyed, and of all my ancestors, whoever they were and whatever they achieved. I will tell my children what they are, and I hope that in the years to come they are interested in my quest and share my pleasure at the results.

NOTES

- This story was written with the assistance of Sanjay Sircar, who notes: 'I encouraged R.B. to tell me his story, which he did slowly and painfully in fragments that I knitted together over a couple of years'. The following notes are Sircar's.

- Park Circus in general, and Circus Avenue (like Royd Street, Elliott Road, Wellesley Street, Ripon Street, etc.) was traditionally (and still remains to some extent) an Anglo-Indian residential area at the furthest end of central Calcutta (Kolkata), some times looked down on as a 'phiringi', that is, mixed-race ('Frank', 'feranghi', Portuguese mixed-race, any European-mixed race) or phiringi-cum-Muslim one by the Bengali middle-classes.

- The term Anglo-Indian once meant 'British-inIndia', but that is no longer its predominant meaning. It is also (incorrectly or confusingly) sometimes used to refer to people of South Asian origin in the UK. 'Indian Writing in English' was a phrase specifically invented to avoid using the phrase 'Anglo-Indian'.

- 'Chi-chi', for things and people Anglo-Indian, pronounced with the 'ch' as in 'Charles', and possibly deriving independently from 'Chhi!' or 'Chhi-chhi!', anejaculation of disgust in many languages in both North and South India, was not heard in India in my own childhood (1955 ff.), though we knew what it meant. It should probably be distinguished from the phrase rendered in the same way but from the French for 'a curl of false hair', pronounced 'shee-shee' — though there may have been some interpenetration of the first meaning by the second.

- Many Anglo-Indians claim descent on the lost 'distaff side' from Indian nobility of one sort or another — sometimes a princess saved from committing suttee on a funeral pyre: see the very peculiar form of this motif in Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days, where it is used for a Parsi—Zoroastrian—wife of a raja (suttee is not a Parsi custom). Some of these claims maybe true, others wishful thinking.